Light, Dark and Bright: Ghosts of the Mosaicoral Empire Kingdom - August 2022

A mosaic is an image made up of pieces of other things. Uniquely shaped, each part of a mosaic tells its story of the place it has come from, as it plays its part in the new story of the whole. While a mosaic may look fractured up close, being made up of broken or irregular pieces, its aesthetic comes from the ordering of those parts into a pleasing whole.

Like a mosaic, many of Kurt Bosecke’s works have the quality of being compositions made up of differently shaped parts. Up close, lines may appear to hover and figures to distort; however, from a distance, the ways in which the artist has organised the elements of his compositions can be better seen.

Certain motifs, characters and subjects crop up repeatedly across Bosecke’s prolific artistic career. From early teenage texta drawings to highly developed recent works on canvas and other mediums, through determined revisitation and redrafting which honed his extensive mark-making ability, we see these ‘pieces’ take shape, becoming bolder, more confident and specific.

Some fascinations are evident from the very beginning, such as the pop culture that has captivated Bosecke since childhood when he would pause shows to draw a particular scene, often zooming in on a particular detail. Cartoons, TV, movies have provided a constant stream of inspiration, as have encyclopedias, with their wealth of facts and realistic depictions. Long-term engagement with these sources has shaped the artist’s approach to the conventions of 2D space, as suggested by Bosecke’s ongoing negotiation with outlines in his practice - sometimes emphasised, at others overpainted to the thinnest margins.

Across all his work is a tendency to abstraction - not just arrangements of abstract shapes themselves (at which he is highly proficient, generating complex and sophisticated compositions, often at scale), but also the process of making the figurative become abstract through analysis, distillation and stylisation of forms. Interestingly, Bosecke doesn’t think in terms of abstraction, titling his works of shape and colour works in terms of imagined, extrapolated or long-overpainted scenarios.

Many of his works take feelings as the subject, naming them in the title, suggesting a viewpoint in which we are looking in on a moment of intense emotion for another, a chance to regard a tiny but significant slice of emotional life. The centrality of strong feelings in cartoons and movies, shown in the familiar, recognizable freeze-frames of emotion - blind rage, ecstatic joy, quavering fear, etc - seems to have provided a bedrock of validation that continues to be productive for Bosecke.

The world underwater is an enchanting subject for Bosecke, who is a keen water man. At times, the artist will revisit video footage from his aquatic adventures to freeze and zoom in on key moments which feed into the worlds in his artworks. Recently, he has been conjuring underwater scenes from the greatest reference text of them all, his capacious memory bank. Bosecke’s strong patterning drive finds a commonality in many natural forms found underwater, from the shapes of curving corals to the brightly contrasting colours of the nudibranch.

Stories of myth and legend are a key set-piece in Bosecke’s mature practice. Mythic worlds provide complex settings and common characters which are frequently reinforced in pop culture, creating a currency around myth and legend as story elements in the Bosecke mosaic. The particular legend of King Neptune, the undersea god, is a favoured subject, appearing with increasing complexity in many paintings and drawings. Ruling over his bustling underwater world, filled with curious ocean creatures and sunken treasures, Neptune offers something of an ideal subject for the artist: rich with satisfying underwater complexity and the challenge of resplendent detail, anchored in the comfort of familiar mythic archetypes.

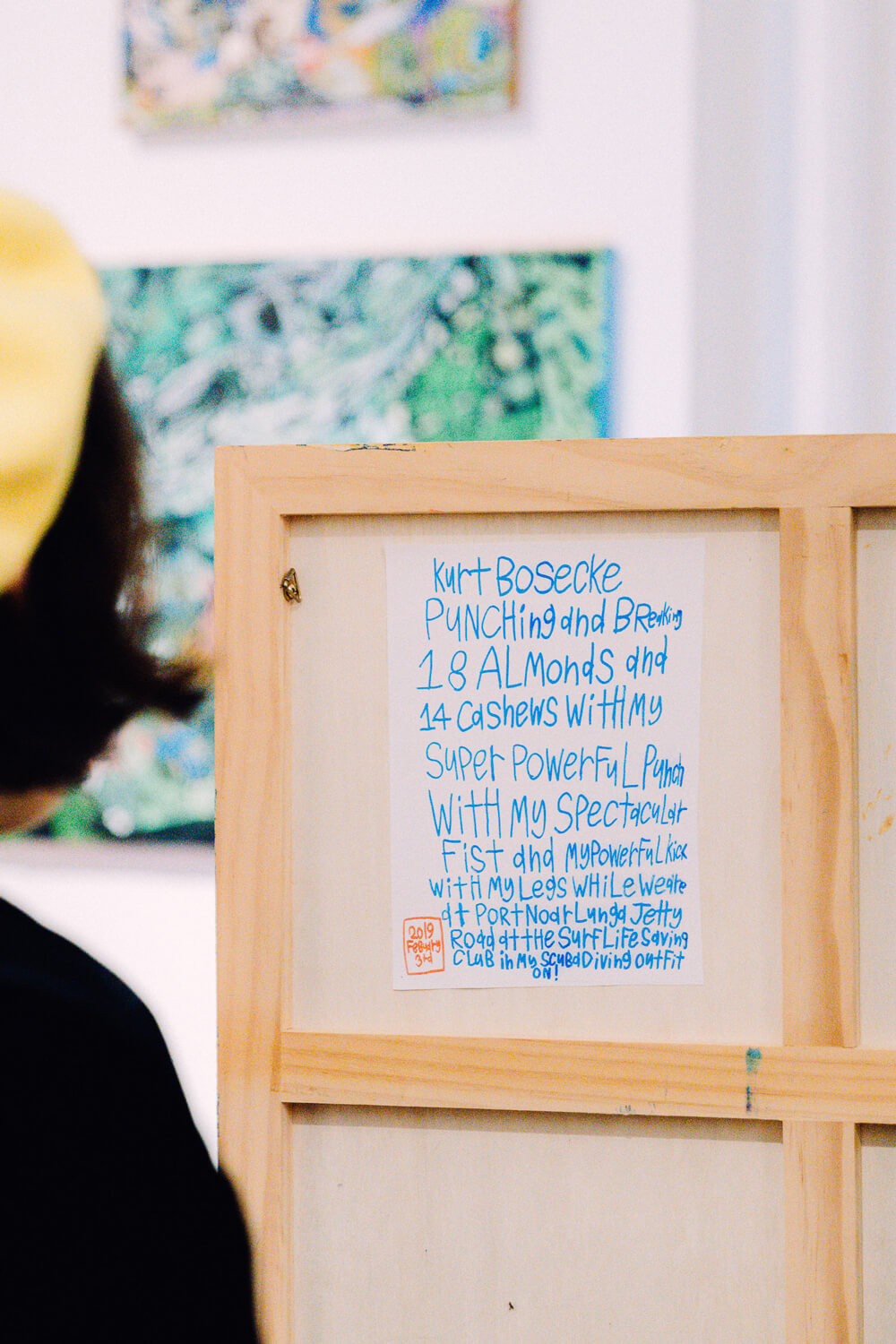

Another key strand in Bosecke’s practice is the self-portraits, which initially appear aesthetically quite different to the more placid, contemplative gaze of his animal studies, underwater kingdoms and abstract works. The self-portraits tend to be worked quite rapidly, compared to the methodical construction of other works, being more about the immediacy of mark-making and the always-available sitter, the artist himself. With himself as the subject, the artist is able to explore more mischievous territory where scary themes are approached with an attitude of cheeky playfulness.

In the self-portraits, again, we see an influence of visual media like TV and cartoons where “the bad guy” is clearly telegraphed through an array of exaggerated emotional expressions: in many scenes, Bosecke is situating himself as the villain in a drama of his own imagining. Thus what could potentially look like slightly disturbing self-portraiture tinged with incipient violence is in fact something more playful, a platform for the artist to express himself using himself, in various guises and poses, as the antagonist or anti-hero.

Bosecke delights in the richer, darker worlds of the villain and the monster, the freeing, transgressive feeling of inhabiting a terror-inducing form (often complete with his own claws and a hyper-muscled physique). In addition to the scary bestiary he surrounds himself with (snakes, lions and bats), at times in these self-portraits he appears to be turning into an animal himself, depicting himself with hairy animal bodies, legs, ears and fangs. Either the constraints of reality are too narrow, the opportunity to play with and extend the idea of the portrait is too strong - or, more likely, it is some combination of both that explains the ample playground Bosecke finds in the edges between fantasy and reality.

It may be so that all artworks are to some degree self-portraits. In the case of the spectator looking at Kurt Bosecke’s artworks, what we see are a collection of pieces of the artist, each individually crafted in some way over the years, brought together in different configurations with the mortar of the artist’s imagination.

Danni Zuvela